Chapter 15.1 Solving matrix games

In order to model a strategic interaction as a game we need to specify the set of players, strategies, and payoffs. The matrix representation can be particularly useful for simultaneous games of two players with a finite number of strategies. This just means we have two players each choosing their actions without observing what their co-player is choosing. And we can concisely list all their actions in the game. In a typical game matrix one player will choose strategies represented by rows of the matrix and the other will choose strategies represented by columns of the matrix.

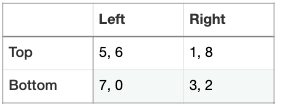

For a concrete example I like to choose two players, Row and Column, each with two strategies. Row player chooses either the Top row or the Bottom row and Column player chooses either the Left column or the Right column. Payoffs in the game are represented in cells of the matrix with the first number corresponding to the payoff to the Row player and the second number to the Column player. So if the payoffs are (5, 6) we know that as a result of their combination of strategies, Row player receives a payoff of 5 and Column player receives a payoff of 6. I’ll place this in the upper left cell of the matrix indicating that the payoffs (5,6) result when Row player selects “Top” and Column Player selects “Left”. We can state this more concisely using the strategy profile, (Top, Left) which reports the outcome by specifying the strategy used by each player in the game.

Now that we have formalized the game matrix we need to come up with a way to solve it. In order to do so we need to specify our solution concept—our convention for predicting the outcome of the game. There’s many solution concepts but for now let’s focus on the most well known: Nash equilibrium. A strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium if both players are best responding. So how do we know if someone—much less both—are best responding?

First a crucial definition: A strategy is a best response if it delivers the highest possible payoff given the strategic choice of your co-player. Row has a choice to make when Column selects “Left”: either play “Top” or “Bottom”. Since “Top” yields a payoff of 5 while “Bottom” yields a payoff of 7 to Row player, it’s best for Row player to play “Bottom”. This is Row player’s best response to Column player’s choice of “Left”. What if Column player selects “Right”? Now “Top” yields a payoff of 1 while “Bottom” yields a payoff of 3 so Row player best responds by using “Bottom”. Actually in this particular game, Row player has the same best response to both potential selections by Column: Row best responds by playing “Bottom”. This means that “Bottom” is a dominant strategy for Row player. Bottom dominates Row’s choice of Top because Bottom is always better.

What about for Column player? If Row selects “Top” we expect that Column should play ‘Right’. For Column player, “Right” is a best response to “Top” because 8 > 6. And for Column player “Right” is also a best response to “Bottom” because 2 > 0. Similarly “Right” is a dominant strategy for Column player because it’s always Column’s best response.

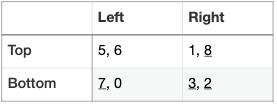

It can be helpful to label the best responses we’ve found in the matrix itself. I like doing this simply by underlining the payoff that goes with the choice that’s a best response:

For this game there’s a single outcome where both are best responding: (Bottom, Right) which is therefore a unique Nash equilibrium in this game. Note that this is the cell where both players have an underline beneath their payoff number.

A few crucial points:

(1) This process explores the hypothetical outcomes for a player given the potential choices of their co-player. We’re considering a simultaneous game meaning that neither player observes the choice of the co-player when the game is actually being played. However for the purposes of finding best responses we consider how the player would want to respond if they knew.

(2) In seeking a player’s best responses we focused only on their own payoffs. We ignored the co-player’s payoffs entirely.

(3) Both players have a dominant strategy in this game but that’s not true in general. Players will always have best responses but need not have dominant strategies.

(4) The Nash equilibrium doesn’t give the highest payoff in this particular game. But that’s okay, Nash equilibrium requires only that both players are mutually best responding.

5) This game is actually a Prisoner’s dilemma because (1) both players have a dominant strategy and (2) joint payoffs are higher when they both play their non-dominant strategy (note that 5+6 =11 > 3+2 = 5. Note further: 7+0 = 7 and 1+8=9 lie in between 5 & 11).

See the video walk-through right here: